Reflection #71 (28th May 2023 at Essex Church / Kensington Unitarians)

These days, people quite frequently ask me to explain what Unitarianism is, and how it relates to the Christian tradition, and other better-known religious paths. All sorts of people ask; often in settings where we don’t have a lot of time to talk and we know we’ll probably never meet again.

On days when I get a taxi home from church the cab driver will almost invariably ask “what sort of church is that then?” (and often they’ll follow up with something that amounts to “is it a proper church or just one you made up?”… which is a conversation for another day perhaps).

And just this week we had a bunch of medics from the Physician Response Unit in our living room – this is the mobile A&E team which more usually follows the air ambulance around as a ground crew – they were sent out to give my dad, who is in the midst of immunotherapy, some treatment at home (so as to avoid taking him into hospital where he would be at increased risk of infection). And while they were doing their thing – marvellously, miraculously taking care of my old man – one of them struck up a conversation which rapidly took us deep into the same territory. Remarkably, this paramedic had heard of Unitarians, he had some thoughtful questions to ask about our way of doing things, and (without prompting) he noted the similarities between our outlook and his own.

And in the last few days I also had a string of emails from an inquirer looking for a spiritual community and asking about our position in relation to Christianity and to other faiths. I did my best to answer. But none of these conversations lend themselves to a simple one-size-fits-all response I can just trot out. Everyone brings their own experience and prior understanding to the question, they have their own concerns about life and the living of it, and I need to try and tune in to all that context and subtext – as best I can – if I’m to do a good job of representing our Unitarian faith to others, and do so authentically, while framing my answer in a way they are likely to be able to hear, understand, and connect with.

The piece I just shared, ‘Found in Translation’ by Robert Hardies, has something to say about all this, I reckon. The sermon that it came from was preached nearly 20 years ago now – I must’ve first read it not long after that – I know it made a big impression on me (especially his claim that ‘Pentecost is the creation myth of Unitarianism’) and shaped my subsequent understanding of how we Unitarians use religious language and symbolism, how we must practice ‘translation’ in order to get over barriers of resistance and incomprehension, and how we make a habit of reaching out to each other across apparent differences in language and culture, knowing we will all be enriched by the exchange.

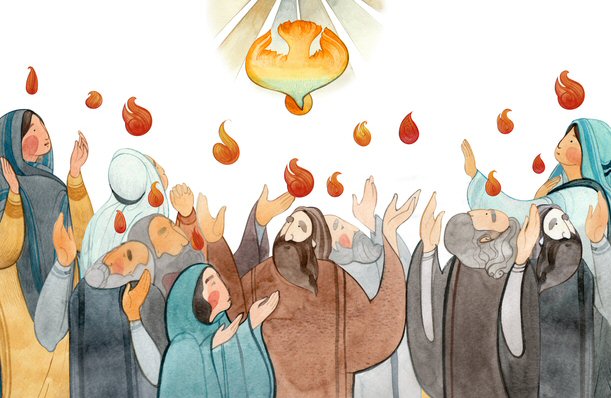

I wonder, what did you hear in the story of Pentecost, from the Book of Acts, that Antony read for us earlier? What resonances does it hold for you? What leapt out of it as an insight you will take away?

Today we heard a modern rendering of the story, taken from ‘The Message’, quite a free translation. Still, some of the language might come across as jarring or alien to Unitarian ears. Maybe you tense up on hearing the call to turn to God, and change our life, so that our sins might be forgiven, or the pronouncement that the spirit will come down upon ‘every kind of people’ and cause us to prophesy. Perhaps, quite understandably, you associate this sort of language with other churches, encounters with other religious traditions, that have been hurtful or even traumatic for you personally in the past. This sort of resistance is entirely legitimate and perhaps some of us just can’t go there. Not today.

But I’m going to encourage us to play with the text, with the story, and try this practice of ‘translation’ together. Let us reach out across time to the people who were there, having that experience, and to those who originally handed it down, then wrote it down, then translated it again and again, until this rendition of this particular – strange – story reached our ears and eyes (and mind and heart) today. What can we connect with, in this tale of Pentecost, despite the gulf between their context and ours? I often say that Unitarians ‘seek wisdom from wherever it can be found’ and, for all their flaws, and complex baggage, ancient texts are a valuable source of collected human experience we can draw on. So what can we draw out of it, learn from it, to help us live our lives here and now, in the 21st century?

One thing I take from the Pentecost story is that God speaks in a multitude of languages to human beings. Of course, the word ‘God’ itself may be an obstacle to some! Feel free to translate to ‘Love’, or ‘Spirit’, or ‘the Cosmos’ or ‘The Good’ (as favoured by Iris Murdoch) perhaps and see if the story makes more sense to you that way. So: God, or Love, or the Spirit, or the Cosmos, or The Good, speaks in a multitude of languages to human beings. We humans have such a diverse range of personalities, temperaments, learning styles, preferences – however you want to characterise it – and are situated in contexts shaped by culture, history, geography, climate, and so much more. Inevitably we each have a ‘mother tongue’ – metaphorically speaking – a default way of understanding the world and speaking about it that we’ve grown up with. Even if we weren’t brought up in any particular religious tradition, we will each have our own unique approach to interpreting the world as we move through it, our own way of seeing and engaging with life’s ultimate questions, and speaking about such matters too. There are very many religious and spiritual paths, each rich and transformative, that can and should coexist. There’s not just one right way. Which is not to say that ‘anything goes’!… rather that some deep truths about life and how to live it can (and must) be expressed and communicated in diverse ways. In the Pentecost story one unified reality is channelled, heard, and understood by each in their own tongue.

This leads on to another learning I take from the story: That there’s a lot to be said for being religiously bilingual – even multi-lingual – yes, we each have our ‘mother tongue’, the mode of expression which comes most naturally to us, both in our speaking and our listening – but if we extend ourselves a bit towards others, if we work to become at least conversant in alternate forms of religious language, this will almost certainly open us up to whole new worlds of wisdom, understanding, and connection. Something that comes up a lot in Unitarian circles is that some of us struggle with God-language – perhaps we’ve got a particular understanding of what ‘God’ means, and we’re sure it’s something we don’t believe in, so we object to using it at all – perhaps we are still working out our own theology and we’re hesitant to dabble in such language when others seem so much more certain about what it means than we are. But, ultimately, people on both sides of this language-divide are involved in the same sincere and pressing questions about truth, meaning and purpose, about life and how to live it. It is important that we don’t let our differing languages become a barrier to sharing in the struggle. Instead, let us make a habit of reaching out, beyond our little niche, in a spirit of curiosity and humility, and seeking to engage with other ways of speaking about the things that matter most in life. It may be that what we hear seems strange, even implausible, or simply hard to comprehend, but often it is possible to sift what we hear for the fragments of wisdom it will so frequently contain.

The third and final thing that I want to draw out about Pentecost is this: for me, this is not primarily the story of a supernatural miracle, a tale of people somehow temporarily taken over by the Spirit, which enabled them to speak in unfamiliar languages and pass on a special telegram from God. In a way, the important bit is what happened next, when the crowd cried out “So now what do we do?” What do we do? And, in answer, we can look to what they did at least as much as what they said. This group of Jesus’ followers came together in community in a way that ‘walked the talk’ of his teachings and example – they urged the people around them to change their lives, to reject the ‘sick and stupid’ prevailing culture of their day, and its oppressive ways – and they tried to live in a new way, seeking to coexist in harmony, and sharing their resources, so that everyone’s needs were met. They ate together. They worshipped together. These people were fired up by the Spirit, filled with conviction and zeal, and with the desire to pass it on – to share this good thing they had found – in an open-hearted way. And people – some people, at least – liked what they saw. And began to join them in this new way of living. That’s a story that inspires me and gives me hope. It speaks to the world we are living in, and the challenges that are facing us now, nearly 2000 years on.

As I draw this short reflection to a close I am going to repeat my invitation and encouragement to you – to reflect on what you heard in the story – and what insights you are going to take away. And I’m going to end with an echo of our opening words from Jan Richardson and her Blessing for Pentecost.

In the place where you have gathered, Wait.

Watch. Listen. Lay aside your inability to be surprised,

your resistance to what you do not understand.

See then whether this blessing turns to flame on your tongue,

sets you to speaking what you cannot fathom

or opens your ear to a language beyond your imagining

that comes as a knowing in your bones,

a clarity in your heart that tells you

this is the reason we were made: for this ache that finally opens us,

for this struggle, this grace, that scorches us

toward one another and into the blazing day.

May it be so, for the greater good of all. Amen.

Sermon by Jane Blackall

An audio recording of this sermon is available:

A video recording of this sermon is available: