Sermon #7 (7th April 2012 at Essex Church / Kensington Unitarians)

The title of this service was nicked from a great mid-90s mystical pop record by the post-punk legend Jah Wobble – maybe a few of you will remember it – when I originally chose the theme I wondered if that title might be inadvertently offensive or at least considered a bit too irreverent or even cocky from a mainstream point of view… It turns out I probably needn’t have worried – in fact once I did my research I was surprised to find that the idea is actually included in the Catholic catechism – which quotes St. Gregory of Nyssa as saying ‘the goal of a virtuous life is to become like God’.

As we heard earlier, there is this strand of thought which says that the task of humanity is to develop into the ‘Likeness of God’ by gradually perfecting our moral character through the struggles of life. A number of great philosophers and religious leaders have identified the path of virtue as a means by which we humans might come to flourish in this way.

So, over the next twelve minutes or so I’m going to offer a whistle-stop tour through some highlights of the history of virtue and flourishing in western thought. We’ll consider some ways in which we might consciously cultivate virtue in our own lives today, and I’ll invite you to reflect on particular virtues you personally value and admire in others, and those you would most like to cultivate and embody in yourself.

This notion that our life’s task is to become more like God has been knocking around a long time. As I understand it, this was one of Plato’s big ideas, later taken up and embellished by his followers – our highest good is to become like God ‘in as far as this is possible’ – and a life of virtue and righteousness is a divine thing which leads to a kind of assimilation into God. These ideas would have been in the air at the time that St. Paul was around, and there are echoes of it in his New Testament writings, regarding Christ as the image of God, and the task of believers to become more like Christ by faithfully imitating his ways. (1 Cor 11:1)

Early church fathers like Ireneaus, Gregory of Nyssa & Clement of Alexandria all took up the idea – and ‘theosis’ or ‘deification’ seems still to be quite a prominent doctrine in the Eastern Orthodox church (though there’s a lot more to the theology involved in all that than I am going to talk about today).

Taking a step sideways – Aristotle is perhaps regarded as the Godfather of virtue ethics. He wrote of the telos of life – life’s ultimate end, the purpose or point of it all – as eudaimonia. I have seen this term translated as “living in a way that is well-favoured by God” – more often it’s understood as “flourishing” – a deep and holistic kind of happiness – living a good and meaningful life.

I’d suggest we might even embellish the idea further and connect it to such notions as self-realisation, fulfilling our potential, and contributing to the common good. Eudaimonia is not about transient pleasure but about a life that is good when considered at as a whole. It may be helpful to imagine yourself sometime in the future, at a very ripe old age, looking back on life – what would you like your life to have been about, looking back over it all, in the end?

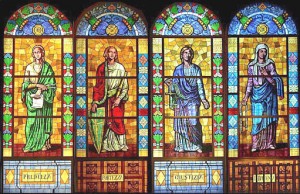

Thomas Aquinas picked up the idea of virtue in medieval times. He defined virtue as a habit or disposition “by which we live righteously, of which no one can make bad use, which God works in us, without us.” Aquinas is associated with the four Cardinal Virtues – justice, fortitude, temperance and prudence – who are depicted on the front of your order of service in stained glass. For Aquinas these four Cardinal Virtues are the principal moral virtues which will help us rise to the challenge of living a good and meaningful human life. Justice is the disposition that gives us concern for others and the common good. Fortitude (or courage) is the disposition that enables us to endure suffering, persist in hard work, and face our fears, for the sake of what is ultimately worthwhile. Temperance is the disposition of moderation and self-control (in a modern context you might think of it in relation to what we consume or give our time and attention to). Prudence is the quality that brings them all together – practical wisdom – knowing how to make good decisions about our actions and the overall direction our life is headed in. Aquinas also highlighted the three very familiar Theological Virtues – faith, hope and love.

At this point I feel the need to echo what we heard from Alain de Botton earlier about the rather uninspiring reputation that virtue has got these days – words such as ‘temperance’ and ‘prudence’ probably don’t immediately stir the soul – and if you were to hear someone described as ‘virtuous’ your first assumption might be that they are going to be joyless, sniffy, buttoned-up, boring – someone who doesn’t know how to have fun. You probably won’t be overly surprised to hear that I haven’t got a lot of time for this view! For me virtue is related to finding a deeper happiness instead of being side-tracked by the superficial. The language of virtue has been somewhat neglected over the centuries but I’d like to see us reclaim and revive it now as a rich and surprisingly practical approach to ethical living in the real world.

A key feature that distinguishes virtue ethics from some of the other ethical theories which have dominated over the last few centuries is that it is focuses on the person rather than the action. The central question is not “what should I do?” (a moral calculation in a particular dilemma) but “what kind of person should I be?” (a life-long project of personal moral development). By becoming a virtuous person, and developing good habits and dispositions, the idea is that in any given situation the right action will come to you as second nature. This is not to suggest that it comes easily – virtue ethics acknowledges the complexity of the moral life – sometimes different virtues will seem to conflict with each other and point in different directions – and part of our task is to integrate the different virtues, using practical wisdom, as we live them out.

So – let’s move from theory to practice – how do we go about becoming more virtuous? Some virtues may come naturally to each of us but others may be more of a stretch. One way to think about cultivating virtue is to compare it with acquiring a practical skill or art – like learning to play the piano, for example – in general virtue is something we learn by doing. It takes conscious awareness – remember the words of the Buddha from our meditation earlier: ‘as we think, so we become’ – and it takes a great deal of practice and persistence. To start with it might feel as if you’re just going through the motions, but by acting ‘as if’ we are virtuous, we can get ourselves into a virtuous circle and reinforce our good intentions. Sometimes you might just have to ‘fake it till you make it’.

Virtue is not just a behavioural habit though, but an enduring disposition of character. It needs to take root in you, so that you think, feel, desire and perceive virtuously, in the ideal case, being able to reliably discern what is good and virtuous, not just doing the right thing. If we want to become more virtuous ourselves, one way to go about it is to emulate a virtuous person. Looking to the lives of great religious teachers, saints, or moral heroes, can inspire us to live well ourselves. Many people look to Jesus as the ultimate moral example and attempt to follow in his ways. From reading the gospel stories we might choose to focus on compassion, forgiveness, and humility. Moral heroes need not be well-known, historic figures. We can also learn by emulating those good people we have been lucky enough to encounter personally in our own lifetime. Maybe it is a bit less intimidating to aspire to be like those virtuous souls whose life circumstances are a bit closer to our own, whose very ordinariness and imperfections we well are aware of, as well as their goodness.

Now, Aquinas gave us four cardinal virtues, and three theological virtues, but as we think about these inspirational characters they may bring to mind many more traits that we consider to be virtuous. In your order of service there’s a little pale green sheet headed ‘One Hundred Virtues’ and of course even that list can’t hope to be comprehensive… but it’ll do to be getting on with! This list is taken from the website of a great organisation called The Virtues Project – nothing to do with the recent initiative by Alain de Botton – this is an educational project that’s been going for over 20 years now, in over 90 countries, and which has been commended by the Secretariat of the United Nations as a ‘model global programme for families of all cultures’.

The Virtues Project draws on sacred traditions from around the world, and offers multi-faith resources for virtues education, with the stated aim of giving children a greater sense of meaning and purpose, in the hope of reducing violence globally. Cultivating virtue is not just an inward exercise in self-improvement. It’s about making a better world.

You might like to cast an eye over that list for a few moments… and consider the following questions:

(there are spaces on the back for you to jot down your answers if you like – that’s why you’ve got a pencil)

Think about someone who you find inspiring or heroic. Which virtues do you most admire in them?

Think about somebody you are close to. Which virtues do you most admire in relationship?

Think about the world we live in today. Which virtues do we most need to cultivate in our society?

Think about your own life as it has unfolded so far. Which virtues are most characteristic of you?

Think about the person you aspire to become. Which virtues would you like to focus on cultivating in yourself?

Perhaps to finish off you might like to choose just one of these virtues you are drawn to and pay special attention to that quality in your own life in the days and weeks to come.

Being fully virtuous does seem to be an ideal that we can aspire towards but can never quite achieve. However, by setting our aspirations high, we may find that even when we fall short we will have stretched ourselves in the direction of the good… towards God.

For me the cultivation of virtue is a religious task, best pursued in a supportive spiritual community like this. So let’s keep on nudging each other along on the path of virtue, and encouraging each other to be the best we can be, in the circumstances in which we find ourselves. May we all flourish together – and live good and meaningful lives – for the greater good of all.

Amen

Sermon by Jane Blackall

An audio recording of this sermon is available: